Category file: Psychoanalysis in Madrid

Loss, to make room for the new

Stephen Grosz, a British psychoanalyst well-known to many psychologists in Madrid who have read his articles in El País, was recently interviewed by Tim Black on his book The Examined Life.

It is fairly unusual for psychoanalysts to write books or articles in such a way that the discipline may be understood by those unfamiliar with the field, and Grosz has done so remarkably well. The success of his book, and how well received it has been, attests to this fact.

In the interview, Grosz touches on his intellectual background and on the relevancy of Freudian thought today. He seeks to avoid pseudo-knowledgeable psychoanalytical jargon and aims to express what is essential to Freud’s discoveries –– notably a method of listening, without preconceived ideas, to what patients say in order to afford them a truthful view of their inner selves.

One of the central ideas of The Examined Life, and Grosz’ interview, is the importance of developmental arrest –– how not being able to lose something can freeze an individual in a state that doesn’t allow them to grow, develop deeper relationships, or gain new capacities. As Grosz puts it: “It’s only by letting go that you will make space for the next phase”.

Through the use of the evocative metaphor of haunting he describes how psychoanalytic treatment summons up, in a way, the ghosts in the patient’s mind. Ghosts that have never had a setting where they could be confronted, and that haunt the patient’s life with their uncomfortable presence.

Psychoanalysis offers them that setting, calls them into the awareness, and faces them squarely. Only then can they be put to rest.

Read Grosz' full interview.

What is psychoanalysis?

The Toronto Psychoanalytic Society (TPS) has recently published some informative videos on psychoanalysis, who it is most suited for, and what distinguishes it from other kinds of psychotherapy.

In the interview here above, Susan K. Moore, a member of TPS, interviews professor Don Carveth, Training Analyst and ex-Institute Director at TPS, on the subject of what psychoanalysis is.

The conversation touches on what kind of psychotherapy psychoanalysis is, what type of person may seek out treatment, the difference between psychoanalysis and cognitive-behavioral therapy, why the unconscious is important, how dreams are a means to access the unconscious, and the way defenses work, amongst several other topics.

The interview continues on some of the many developments of psychoanalysis since Freud’s death: for instance, how subsequent analysts explored the earliest stages of mental development (Klein and Winnicott); and others discovered, and experimentally studied, the effects of attachment and loss (Bowlby).

Professor Carveth, having been the TPS Institute Director and taught extensively, finishes the interview talking about the importance of teaching and learning about all psychoanalytic perspectives in order to be able to access the widest range of patients’ psychic realities.

This stance is shared by many IPA Institutes and is also the case at the Madrid Psychoanalytical Association, where psychologists and psychiatrists who train there will be exposed to the whole range of theoretical and clinical thought.

Understanding and treating psychological inhibitions

Inhibition expresses itself in many ways. It is probably one of the most common clinical symptoms psychologists come across, as well as one of the most frequent limitations with which some individuals, who believe that they are relatively free from difficulties, live with unawares.

Inhibition consists in an incapacity to freely express a wish or a natural ability; the individual is diminished by the inhibition and cannot fully develop himself or herself. This generally entails a significant limitation in the enjoyment of their life.

Inhibition frequently manifests itself in sexuality, sometimes annulling it completely, as well as in the fear of facing conflicts, leaving the person defenceless. It is not unusual for intellect, attention and/or memory to be hindered by it, which can obstruct educational and professional development.

It is sometimes linked to food, drastically reducing the capacity to nourish oneself; it can appear when one has to speak in public, leaving the person mute and confused; it is also well known amongst people who play sports and who can suddenly find themselves incapable of competing… The list is potentially endless.

Where does it come from?

An introductory overview of psychoanalysis

The International Psychoanalytical Association ––founded by Freud in 1910, and federating 72 constituent societies worldwide–– has recently published an informative online article: "About Psychoanalysis".

It explains the origins of psychoanalysis, what it is for, Freud’s discoveries, the major schools of thought, the setting, how analysts train, ethical principles, and many other areas.

Written by Cordelia Schmidt-Hellerau in Boston, Gábor Szõnyi in Budapest, and Raul Hartke in Porto Alegre, all three Training Analysts of the IPA, the article is an unbiased introduction to the field for those who wish to know more.

Read the article.

Who can become a psychoanalyst?

In Spain, as in most of the Western world, current legislation requires that those who wish to study psychoanalysis must previously have undertaken studies in psychiatry or clinical psychology.

These preceding studies guarantee a solid enough grounding in psychopathology, differential diagnosis, brain functioning, psychopharmacology, research methods, treatment options and social psychology that are essential for clinical practice.

However, those studies are not enough to be a psychoanalyst. There are certain personality traits, of those who wish to undergo further training in order to become psychoanalysts, that must be present in order for that wish to become a reality. These traits are not necessarily fully consolidated at the beginning of an analyst’s training, but there has to be at least a core that can be developed.

Those who wish to train in psychoanalysis in Madrid, in the Asociación Psicoanalítica de Madrid, will go through interviews where these qualities will be assessed, as well as the depth of self-knowledge acquired through personal analysis.

What are they then?

Emotional and intellectual honesty:

Every psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy rests on the quest for finding the patient’s inner truth, whatever it may be. This comes with a requirement of honesty on the patient’s part, but also on the analyst’s. Due to the sensitive material that they will work with and the trust it requires, the analyst must be willing to recognize that he is not infallible and can make mistakes, and he must also be willing to face whatever may arise during the treatment –– analysis is not an ascetic intellectual exercise and strong emotions will most likely appear at some time.

Who benefits the most from psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy?

There are currently many schools of psychotherapy –– such as psychoanalysis, cognitive-behavioural therapy, systemic therapy, humanistic therapies, etc.–– that are based on divergent theoretical foundations, and offer different treatment modalities.

Although historically each one of these schools has claimed, or sometimes still claims in certain cases, that it is valid for all those who seek psychological help, empirical evidence and the combined years of experience of many practitioners show us that this is not a verified fact.

In addition to the specific expectations of the people looking for assistance, their individual personalities will lead them to be more receptive to one kind of help than to another. The most noteworthy differences between people when it comes to choosing a psychotherapeutic treatment will manifest through their tolerance to frustration, where they locate their problems, and their degree of autonomy.

When it comes to psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy, there are certain personality dispositions ––that do not necessarily express themselves in all situations, but are nevertheless central to the person’s psychological makeup–– without which it is difficult for someone to be able to benefit greatly from this type of treatment.

What are they?

Let’s begin with the fact that psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy rest on some fundamental principals, mainly that:

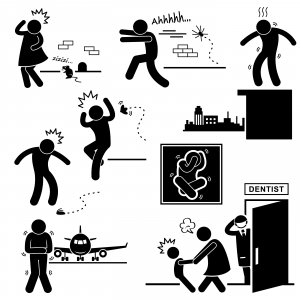

Phobias: diagnosis, etiology and treatment

The diagnosis of a phobia is usually fairly clear. A phobia is any irrational fear of objects, animals, situations or spaces that are not objectively dangerous.

One is afraid of something objectively dangerous ––a lion, for instance–– but one has a phobia of something objectively harmless, a mouse. The phobia does not come from the phobic object in itself but from what that object stirs up in the mind of the individual that suffers from the phobia.

Phobias are a very effective way for the psychic apparatus to get rid of the inner anxiety from which the subject suffers. Instead of feeling that the anxiety and the danger are within, the phobia allows the subject to locate the source of anxiety outside, where it can be avoided.

For instance: an individual who is very afraid of her own aggressiveness may develop a phobia of dogs (onto which she can attribute the idea of aggressiveness). Then she can avoid dogs and, by doing so, be free of anxiety. The fear of herself has become the fear of something else that can be avoided. Needless to say, all of this happens unconsciously, there is no conscious intentionality in the creation of a phobic symptom.

Precisely because of the fact that phobias allow the individual to locate the source of danger on the outside, many people can live with their phobias without great difficulties since they simply avoid their phobic object, and thus avoid anxiety.

However, the situation becomes more complicated when avoiding the phobic object starts to severely restrict the individual’s freedom. It is not uncommon in certain cases for phobic objects to multiply, progressively invading and limiting the subject’s life more and more.

Psychoanalysis and fanaticism: a conference in Madrid

Introduction to Fanatical Mental Functioning

Conference given at the Círculo de Bellas Artes, Madrid, 8th of April, 2015

Definition:

Fanaticism is a belief or a behaviour that implies an a-critical and zealous attitude towards political, religious or ideological causes, and that insists on very strict standards with no tolerance for different ideas or opinions. The fanatic knows that The Truth is on his side and he hates any other point of view. This said, we must not forget that we all need certain irrational beliefs and convictions in order to function in our lives and we can all become a little fanatic when our beliefs are questioned.

Etymology of the term:

The word fanatic etymologically comes from the Latin word “fanum”, the Roman temple where the oracles went. It was in these temples that the cult of the goddess “Ma Bellone” was celebrated. She was a figure of Roman mythology, the goddess of war, who represented the horrors of war more than the heroic aspects. The sooth-sayers that interpreted the omens, and the goddess’s priests, inspired by the divine, would whip themselves up into an ecstatic religious frenzy where they would contort themselves furiously, cutting themselves with swords and axes, letting their blood flow. These sooth-sayers were called the “fanatici”. “Fanum” also has the same root as “vates”, the prophet, and the “fanum” is the place of prophecy. The cult of “Ma Bellone”, was later incorporated into the cult of Cybele, the cult of war and patriotism. Devoted to a goddess, the “fanaticus” speaks in her name and with her authority.

We should note that, at first, the word “fanaticus” was not pejorative, the “fanatici”, with their feverish contortions and religious fervour, were the means through which divine wishes and destiny could be known. It was only later that their agitated states and incoherence were deemed suspicious by Christianity and little by little they were lumped together with paganism, Muslims and certain branches of Christianity.

Two kinds of fanatics:

Our colleague Manuel Martínez talked about this last month so I’ll be brief. We can distinguish between the original fanatic, the fanaticizing one, and the induced fanatic, who is fanaticized by the original one. The former has the authority that allows him to give his troops (the induced fanatics) the right to overcome the inhibitions created by their moral consciousness. A clear example of this, among many others, is hitlerism, where people who in other circumstances would never have committed those acts were led to commit them. The mental structure of the original fanatic is more complex, more twisted, than that of his followers. The induced fanatics are usually conformists who by associating themselves to the original fanatic can express their sadism without feeling guilt. They seek security by associating themselves with someone perceived to be omnipotent but that security will fall apart sooner or later because the circle of enemies never stops growing and the paranoid system ends up defeating them. The original fanatic is someone who has an enormous, invasive personality with a tendency to make it all about him, obsessed with power and close to being delusional. The induced fanatic is someone who seeks to fuse with a group, lose his individuality and just be part of a greater mechanism.

Treatment of psychological trauma

What is psychological trauma?

Psychological trauma is the result of a painful excess of emotional intensity that shatters the mental functioning of an adult, or that severely distorts the development of a child’s mental functioning.

The most common psychological traumata are generally due to: a) a rupture in the basic feeling of safety; b) a lack of necessary human interaction; c) being the object of excessive or inadequate manifestations of aggressiveness / sexuality.

Though we usually associate the word trauma to something massive and obvious, it is important to note that it can equally result from something small and accumulative.

In the same way that the physiological tissues of the body can handle a certain force of impact without deteriorating beyond their capacity to recover, the mental tissue can withstand a certain quantity of emotional impact without being damaged beyond its capacity to heal. However, beyond a certain threshold, the impact is too strong, and it negatively modifies the physiological and mental tissues permanently.

From this moment onwards, if treatment is not applied, the damage will tend to become chronic and will compromise the rest of the person’s functioning. In the same way that a broken leg, that has not been adequately treated, will seriously limit the individual’s movement ––as well as causing muscular unbalances, and hip and spine misalignments––, untreated psychological trauma will leave the person “limping” emotionally, as well as creating a whole series of compensatory behaviours that will paradoxically worsen the original state.

How does psychological trauma affect us?

Without going into great depths that would be out of place here, we can understand the mind as a processor of stimuli (internal and external) that uses them to maintain itself and to evolve. This processor also needs to discharge the stimuli that exceed its capacity to use them for growth, and this discharging is frequently associated with pleasure (e.g. creative and physical activity, sexuality, etc.) At a neuronal level, every stimulus creates activation in the neurons that has to be processed, absorbed or discharged one way or the other.

New sexualities? A psychoanalytic perspective

The Symposium of the Madrid Psychoanalytic Association (APM) held in Madrid in the Hotel Puerta de América from the 23rd to the 24th of November, 2014.

The subject of the APM Symposium this year was if current manifestations of sexuality are truly new or are they simply variations of the same sexuality that has always existed.

There were two major panelists: Juan Francisco Artaloytia is a psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, Full Member of the APM, who works in Bilboa; Martina Burdet is a psychologist, psychoanalyst, Training Analyst at the APM, who works in Madrid.